Veterinary Cuts: The Problem of Sharps Injuries in Pet Care

Sharps injuries are a worrying concern for veterinarians. A survey sent to members of the Veterinary Surgeons Board of Queensland in 2006 revealed that 75.3% had at least one sharps or needlestick injury in the previous 12 months, while 58.9% reported suffering from at least one contaminated sharps or needlestick injury during the previous 12 months(1). The most common causative devices were syringes (63.7%), suture needles (50.6%) and scalpel blades (34.8%).

Contaminated sharps can infect and further complicate scalpel cuts. According to the Epidemiology of Needlestick and Sharps Injuries in Veterinary Medicine, the most important bloodborne pathogens in veterinary work are Staphylococcus spp.; Pseudomonas spp. (inoculated from the animal skin); pathogens from fine-needle aspirates Blastomyces, Pasteurella spp., Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp. (from fine-needle aspirates); and certain arboviruses or modified live vaccines(2).

The survey shows that these sharps injuries occur regularly, and that veterinarians are aware of the occupational hazards they face every day. The US National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians, www.nasphv.org, has written a “Compendium of Veterinary Standard Precautions for Zoonotic Disease Prevention in Veterinary Personnel” to help vets learn about the risks of their profession (3). The document is recommended and endorsed by the American Animal Hospital Association.

Hierarchy of Controls

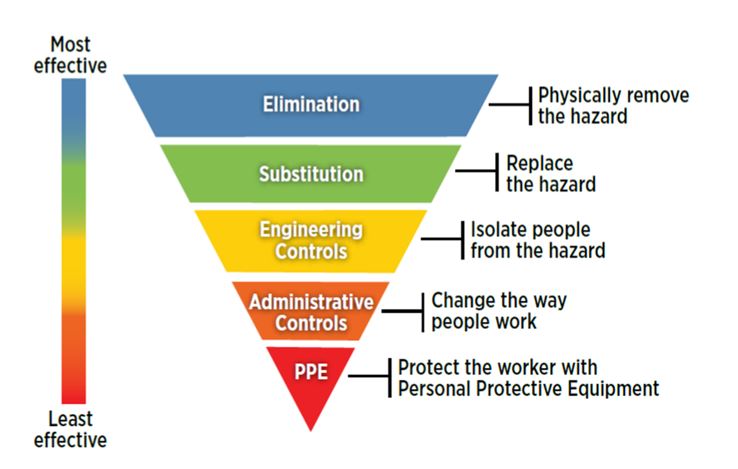

In the compendium, the Hierarchy of Controls sets out a control measure to prevent harm to vets/ to protect against injuries and infection.

According to the document:

- Elimination or substitution of the hazard—In general, this is the most effective measure, as it requires no action on the part of the employee. The hazard has been identified and eliminated. An example would be exclusion of exotic pets or native wildlife from a clinic because of the disease risk; such animals would include macaques and skunks that are associated with a risk of herpes B virus or rabies virus transmission.

- Engineering controls—A veterinary clinic is designed to facilitate infection prevention best practices. An example would be placement of sinks for handwashing in convenient locations.

- Administrative controls—Clinic policies are adopted that mandate appropriate infection prevention practices Administrative controls are there to support and should be implemented with higher control measure such as safety engineered devices Examples would be the requirement for handwashing between patient contacts, no recapping of needles, and rabies vaccination of staff.

- Personal Protective Equipment—This control measure is generally considered the least effective and the last line of defence because it requires the most action from the employee. The use of PPE requires routine adherence to and appropriate use of a variety of equipment and is dependent on employee training. PPE is frequently and appropriately used in veterinary practice when engineering and administrative control options are limited. An example would be using extra gloves (double gloving) to protect you from sharps cuts.

Sharps Injury Prevention

There are also sharps injury risks associated with the usage and containment of scalpel blades. A good way to implement engineering controls to help reduce the risks of these is to use the Qlicksmart BladeFlask EVO Scalpel Blade Remover. It is designed to remove, contain, and dispose of scalpel blades in just one click. It is able to single-handedly remove more types of BP scalpel handles and blades than any other remover including large veterinary scalpels, Barron, bulbous, thick and round handles, hexagonal shaped versions, and even the new ergonomic handles – giving you greater freedom in using any scalpel you want.

To find out more about Qlicksmart safety devices, send us an email at hello@qlicksmart.com.

References

- Leggat, P.A., Smith, D.R. & Speare, R. Exposure rate of needlestick and sharps injuries among Australian veterinarians. J Occup Med Toxicol 4, 25 (2009). http://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-4-25

- Coelho, A.C. Epidemiology of Needlestick and Sharps Injuries in Veterinary Medicine, Occupational Health, Orhan Korhan, IntechOpen, (2017) DOI: 10.5772/66110. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/chapters/52841

- National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians. Compendium of Veterinary Standard Precautions for Zoonotic Disease Prevention in Veterinary Personnel, (2015). Available from http://www.nasphv.org/Documents/VeterinaryStandardPrecautions.pdf