The Hierarchy of Controls and Sharps Safety

Addressing the Hierarchy of Controls Using Sharps Safety

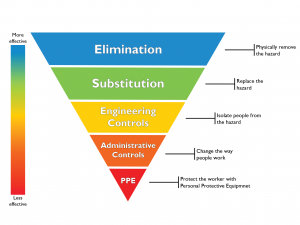

The Hierarchy of Controls is a very effective method for managing hazards in the workplace and should be followed to prevent sharps injuries to healthcare workers. According to Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), it is a well-recognised approach used to address sharps hazards in healthcare settings, as seen in the Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses’ (AORN) sharps safety guidelines (1, 2). This article will therefore explore the Hierarchy of Controls in the context of sharps safety.

The Hierarchy of Controls

Originally developed by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in the United States of America, the Hierarchy of Controls is now mandated in workplace safety legislation and regulations throughout Australia and across the world (3, 4). This approach differs from previous behaviour-based safety approaches, by addressing the initial sources of hazards experienced by workers (3, 4). The hierarchy establishes five levels of hazard control measures, which are prioritised according to their effectiveness. These levels are:

- Elimination

- Substitution

- Engineering Controls

- Administrative Controls

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Elimination

Elimination is the most effective way of ensuring safety, as it involves physically removing the hazard from the workplace. In regard to preventing sharps injuries, facilities should look at ways to eliminate the hazard (sharp instruments) where possible. This can be achieved by identifying and eliminating unnecessary injections and using alternative routes for administering medication, such as through tablets, inhalers, or transdermal patches (5, 6, 7). Additionally, use of sutures for closing skin incisions can be reduced by using adhesive strips, glues or stapling (2, 8). Identifying instances in which endoscopic surgery can occur in place of open surgery is also another elimination technique (6).

Substitution

The next level of control involves replacing hazardous devices and procedures with those that are free from the hazard, to perform the same task more safely. In some cases, elimination and substitution may be combined. Regarding sharps safety, examples of substitution control measures include adoption of needle-free intravenous access systems, blunt suture devices, and jet injection systems (5, 9, 10). Although most effective, eliminating and substituting a device is not always feasible, which is particularly the case in surgical settings. As sharps such as scalpels are required to make incisions for surgeon access, engineering controls are the most effective control measure available.

Engineering Controls

Implementing engineering controls is another effective control measure, as it enhances the safety of traditional devices. Specifically, engineering controls incorporate safety mechanisms designed to either isolate or remove the hazard from the environment (6, 8). It is therefore most useful when alternative instruments or procedures are not adequate or appropriate. To reduce the risk of injuries from sharps, engineering controls work to isolate sharp instruments. Examples include safety-engineered devices such as syringes that retract, sheath or blunt, as well as scalpel blade removal and sharps disposal systems (9, 10).

Not All Safety Devices are Equal

Selection of the correct safety device is also important, with increasing evidence demonstrating superior safety of passive devices, compared to active devices (11). Active devices require manual activation of the safety feature, whereas passive devices are automatically activated. Qlicksmart’s range of single-handed scalpel blade removers are examples of passive safety devices, as scalpels are removed and contained automatically, ensuring safe removal and disposal. More information about these devices can be found on our website.

Administrative Controls

Administrative controls involve establishing procedures and policies that further reduce the risk of exposure to hazards. They are most effective when used in conjunction with higher levels of the hierarchy. Administrative controls specific to sharps handling include establishing and ensuring compliance to sharps safety policies and procedures, some of which are listed below.

- No direct contact with sharps (2)

- Clear communication when handling sharps (2)

- Using instruments for tissue retraction (2)

- Appropriate sharps injury incident reporting processes (2)

- Avoiding recapping of needles (5)

- Avoiding overfilling sharps containers (5)

- Utilising neutral-zone or hands-free passing techniques (8)

- Ensuring safe disposal of sharps (8)

- Vaccination of staff exposed to sharps (9)

Recent findings highlight the effectiveness of administrative controls accompanied by engineering controls. For example, a 2010 systematic review indicates that the use of a hands-free passing technique and single-handed scalpel blade remover can be up to 5 times safer than a safety scalpel that is inconsistently activated (12).

Staff training on sharps safety and the risks of bloodborne pathogens should also be provided in addition to training on new engineering controls, to ensure that safety devices are implemented and used properly (2, 9, 10). Qlicksmart provides how-to-use videos for all of its safety devices, which can be found on our website and YouTube channel.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Personal protective equipment is considered the final and least effective form of control against hazards in the workplace. This equipment provides a physical protective barrier against hazards. In many instances PPE is unreliable, as it may not adequately fit individuals, fails to protect against some chemicals, may require training and suffers from lack of compliance resulting from discomfort, unfamiliarity, and interference (10). PPE recommended for sharps handling includes double-gloving and protective footwear (8). As failure of PPE means the worker is directly exposed to the hazard, this form of control should only be used in addition to higher levels of the hierarchy (10).

The importance of investing in safety

It is clear that the Hierarchy of Controls is an effective workplace health and safety approach, which can be utilised to control the risk of sharps injuries among healthcare workers. Unfortunately, facilities tend to focus on administrative controls and PPE, as they appear easier and cheaper to implement (13). To reach safety solutions that are more effective in the long-term, facilities should instead prioritise higher levels of the hierarchy. For more information on how we can assist facilities implement more effective control measures to keep staff safe from sharps injuries, contact Qlicksmart here.

About the Author: Annabel Wheatley is a graduating student from the University of Queensland, with a double major in marketing and psychology. She had researched and written about medical safety including risks of sharps injuries.

References

- National Health and Medical Research Council. (2019). Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Controls of Infection in Healthcare. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-guidelines-prevention-and-control-infection-healthcare-2019#block-views-block-file-attachments-content-block-1

- Ford, D. (2014). Implementing AORN recommended practices for sharps safety. AORN Journal, 99(1), 106 – 120. http://doi.org/1016/j.aorn.2013.11.013

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2015). Hierarchy of Controls. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/

- Safety Institute of Australia. (2012). Control: Prevention and Intervention. http://www.ohsbok.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/34-Control-Prevention-and-intervention.pdf?d06074

- Queensland Health. (2017). Risk management. http://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/infection-prevention/standard-precautions/sharps-safety/risk-management

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2008). Workbook for Designing, Implementing & Evaluating a Sharps Injury Prevention Program. http://cdc.gov/sharpssafety/pdf/sharpsworkbook_2008.pdf

- Wilburn, S., & Eijkemans, G. (2004). Preventing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: A WHO-ICN collaboration. International Journal Of Occupational And Environmental Health, 10(4), 451-456. http://doi.org/10.1179/oeh.2004.10.4.451

- Queensland Health. (2017). Perioperative sharps safety. http://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/infection-prevention/standard-precautions/sharps-safety/perioperative-sharps-safety

- Queensland Health. (2017). Developing a sharps safety program. http://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/infection-prevention/standard-precautions/sharps-safety/sharp-safety-program

- Gorman, T., Dropkin, J., Kamen, J., Nimbalkar, S., Zuckerman, N., Lowe, T., Szeinuk, J., Milek, D., Piligian, G., & Freund, A. (2013). Controlling health hazards to hospital workers. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 23, 1-167. http://doi.org/10.2190/NS.23.Suppl

- Freund, A. (2013). Controlling health hazards to hospital workers. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 23, 1-167. http://doi.org/10.2190/NS.23.Suppl

- Tosini, W., Ciotti, C., Goyer, F., Lolom, I., L’Hériteau, F., Abiteboul, D., Pellissier, G., & Bouvet, E. (2010). Needlestick injury rates according to different types of safety-engineered devices: Results of a French multicenter study. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 31(4), 402-407. http://doi.org/10.1086/651301

- Watt, A., Patkin, M., Sinnott, M., Black, R. J., & Maddern, G. J. (2010). Scalpel safety in the operative setting: A systematic review. Surgery, 147(1), 98-106. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2009.08.001

- Moris, G. A., & Cannady, R. (2019). Proper use of the hierarchy of controls. Professional Safety, 64(8), 37-40.