Medication Errors: An Obstacle To Patient Safety

All healthcare professionals strive to provide the safest care possible. Sometimes however, things can go wrong, and harm can be done. As an Emergency Physician for more than 30 years, I have seen many healthcare workers, especially clinicians, suffer from the guilt and embarrassment when their patients experience adverse reactions from preventable medication errors.

Medication errors are preventable human errors, and they are costly.

Each year in the U.S., severe preventable medication errors occur in close to 4 million inpatient admissions and 3.3 million of outpatient visits. A grossly inappropriate 7,000 patients die from preventable medication errors in the U.S. each year, as recorded in the report To Err Is Human.

Medication errors cost a total of $21 billion expenditure every year.

In many cases, looking back at the medication errors hardly goes beyond a comment that “he/she was busy or distracted”. Similarly, looking forward past the events does not raise more than “be more careful next time”.

The truth is, we should not blame the healthcare workers have made the medication errors.

We should look at from a broader perspective of how the medication errors happened, and in this case, the healthcare system.

The Swiss Cheese Model

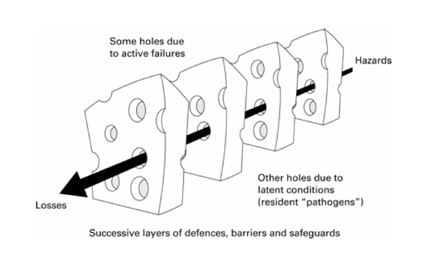

To explain the complex and layered healthcare system and how each healthcare workers could potentially prevent (and cause) medication errors, James Reason proposed the Swiss Cheese Model.

According to this model, a series of barriers are in place to prevent hazards from causing harm to humans. However, each barrier, such as system alarms, administrative controls, surgeons, nurses, etc, has its unintended and random weaknesses, or holes, just like Swiss cheese.

The presence of holes in one of the slices does not normally lead to a bad outcome; but when by chance all holes are aligned, the hazard reaches the patient and causes harm.

Source: Perneger, T. V. (2005). The Swiss cheese model of safety incidents: are there holes in the metaphor?.

My Personal Experience

Still gives me shivers when I remember it – and it was only a Near Miss and it happened a couple of decades ago.

I was working as an Emergency Medicine registrar. I was about to do a ring block on a patients finger to enable me to clean and suture the wound.

The nurse, a good friend of mine, who was assisting me with the procedure, opened the ampoule of local anaesthetic for me to draw up the contents. She showed me the ampoule for me to double-check the name and expiry date etc – something I usually only did very casually, probably as a sign of my “trust” that my nursing colleague would always do it correctly

For some inexplicable reason, I actually did read the name this time. The drug name was in red not blue – it read Lignocaine (lidocaine) with Adrenalin – not just plain lignocaine.

My heart sank, that terrible, sickening cold shiver ran up my spinal column. I looked at the point of the needle on the syringe that was facing directly at the skin on the dorsum of this man’s finger. The skin was already prepared (cleaned with alcohol) and I was about to inject 2 mls on the medial side, 2 mls on the lateral side and 1 ml on the top of the injured finger, as I had done multiple times in the past.

One of the most fundamental rules of Emergency Medicine was that you never, I stress never, inject Adrenalin, which is a vasoconstrictor, into an end-artery organ – like a finger, a toe or a penis. The adrenalin would in theory, vasconstrict the arterial supply (which is good for prolonging the duration of the local anaesthetic), but this could result in the total lack of blood supply to that body party, causing cellular death and necrosis – because no second set of arteries were available to provide the essential oxygen.

The result in this case could have been the patient’s finger might have died and needed to be amputated.

I felt sick then, but managed to correct the error, draw up plain lignocaine and successfully and professional repair the patients lacerated finger.

I felt even worse that night as I unsuccessfully tried to sleep. My mind playing games – what if I had injected the local anaesthetic with Adrenalin?

Would the man’s finger have died?

Would he have been traumatized with the loss of his body image?

Would it have affected his ability to work?

Would I have been sued?

Would I have been sacked?

Would my colleagues have lost respect for me and confidence in my ability to do my job?

I would have expected the answer to all these questions about consequences for me to have been “yes” and I would have had to accept it.

It would have been my fault (concept of self-blame to be discussed in future blogs). I would not have had a leg to stand on.

The inability to sleep went on for weeks, eventually getting less frequent.

Like a classical grief reaction I went through the phases of:

Denial (I am sure it would have worked out okay, the finger wouldn’t have dropped off. This stage was brief, as the evidence of my “guilt” was indisputable )…

Anger (how could I be so stupid? why had the nurse opened the wrong ampoule? why didn’t I routinely check the ampoule details when they were shown to me?)…

Bargaining (what if it was only temporary vasoconstriction? what if it settled without consequence? what if a vasodilator had fixed the problem without any damage to the patient’s finger?) and finally..

Acceptance (my fault, lucky this time, be more careful in future).

….and I would like to reiterate, this was just a “near-miss”!

What would I have felt like if the patient had lost a finger or worse……

Where can it go wrong?

Just how many possible areas where things can go wrong?

It’s actually more than you can imagine.

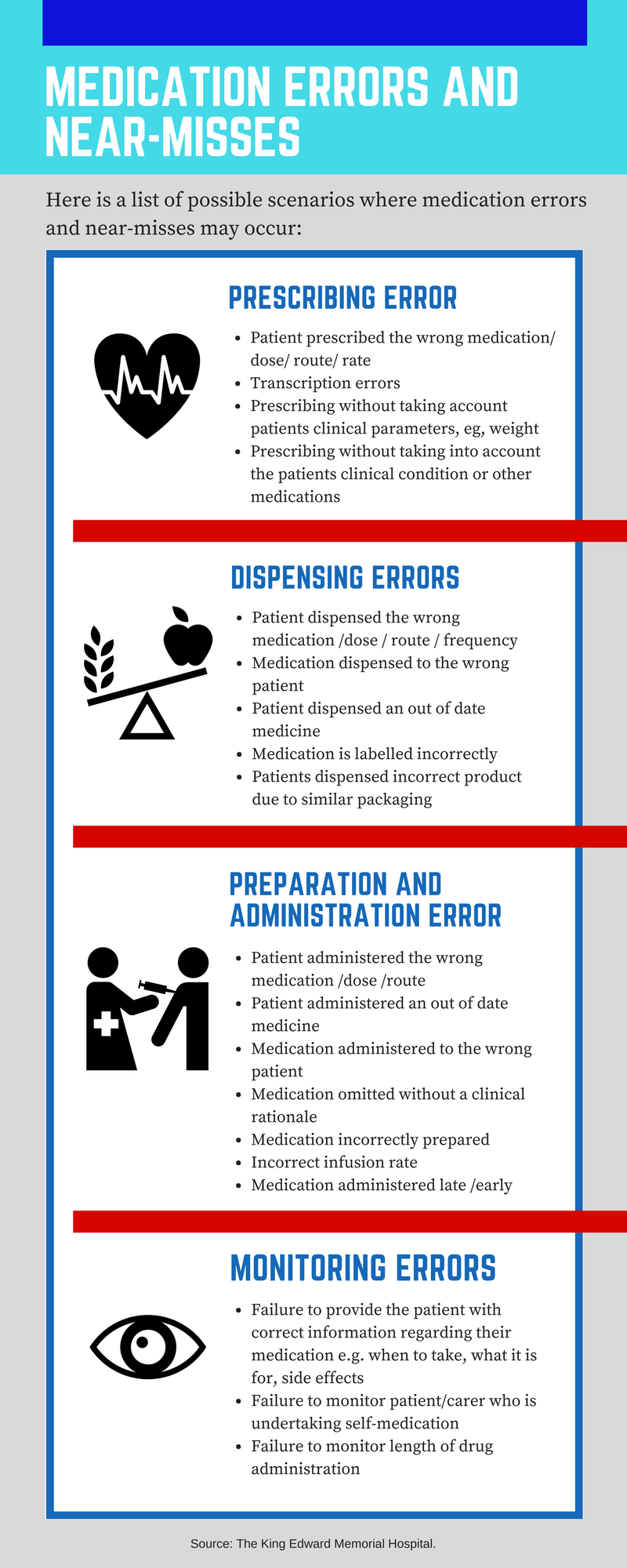

While not exhaustive, the King Edward Memorial Hospital has proposed a list of possible scenarios where medication errors and near-misses may occur, where we have convert into infographics:

Apart from death from fatal medication errors, patients may suffer from short and/or long-term side effects, ranging from mild nausea and vomiting, to prolonged hospitalization or life-sustaining therapy.

Furthermore, healthcare workers may suffer from shame, guilt, and self-doubt from the medication incidents and the hospital may face legal litigations from patients and family members for direct and indirect medical cost for personal injury and mental distress.

What can we do?

To borrow a quote from James Reason, “we cannot change the human condition, we can change the conditions under which humans work”. That can include the countless initiatives worldwide to minimise human and system errors.

Bringing it all together, it takes a little extra effort to pause, think, and double check if everything is alright.

Do you have personal encounters of medication errors and near misses at your workplace? Or do you have any initiatives or tricks that can minimise the possibility of medication errors? Share with us now!

We read every comment.

Dr. Michael Sinnott was involved in clinical medicine for over 35 years before retiring in 2018, the majority of that time was in the Emergency Department. While working in several Australian hospitals, Dr. Sinnott engaged in the education of more than 4,000 junior doctors, 200 registrars, and innumerable medical students.

Dr. Michael Sinnott was involved in clinical medicine for over 35 years before retiring in 2018, the majority of that time was in the Emergency Department. While working in several Australian hospitals, Dr. Sinnott engaged in the education of more than 4,000 junior doctors, 200 registrars, and innumerable medical students.

He has over 40 publications, and is a world-leader in research regarding staff safety in healthcare; particularly scalpel safety. His expertise in staff safety lead Dr. Sinnott to become involved in the development of safety guidelines and legislation in the USA, and safety standards in Australia.

Working with technology dependant children in their own homes, we work to a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). Medication transcribing from bottle to the medication administration record is done with a second person and signed as accurate.

We have a medication handover that must be completed with the parent at the beginning and end of the respite shift, we also follow the 6 rights of meds admin, person, date, time, drug, dose, route.

Our staff have yearly theoretical updates and practical assessments, we undertake bi-monthly audits of the SOP

I believe a portion of these areas are overworked staff, which leaves missing devices inside patients, missing symptoms, missing medicines, and incorrect medication doses.

That said, with the current Coronavirus crisis I can not even begin to imagine what Nurses are having to cope with at this time. Thank you for all you do and we will not forget.

You did not include KNOWN ALLERGY

I was in the past prescribed TWICE an antibiotic that I am allergic to and which is clearly marked on my medical records.

The first time, I was heading gratefully back to my car, eager to go to the chemists to get going on the meds & be cured. I was able to return to reception and ask for a new script.

The second time was in hospital where I was wearing a red wrist band with the name of this drug on it. I had just had surgery and we being given a broad plectrum IV before moving to tablets for discharge. My discharge meds arrived and in it, the very drug I cannot take.

Again, I spotted this and raised the “alarm” . I can maybe get my head around this being done an overworked medic probably whose “go to” drug for this particular complaint is this drug but where was his/her built in re-check against the patient record for known reactions?

How does a prescribing mistake which could be avoided by allergy checking hand corrected before the patient becomes involved?

These days I order online & so do now always double check rather than assume that whats been prescribed it’s right but I’d assume that there are not built in safeguards such as a visual & audio warning sequence triggered if a drug a that a patent is recorded as being sensitive to is attempted to be prescribed?